Mirages in the mountains: Why post 9/11 US strategies in Afghanistan achieved more illusory than real success?

Introduction: The Long War Could Have Been Shortened

More than seven years after the events of 9/11 and the launch of ‘operations’ in Afghanistan, a debate still endures in academic, media and policy circles on whether US strategy and tactics were successful in achieving the proclaimed goals. While one of the immediate over-arching military goals in Afghanistan in 2001- to terminate the rule of the Taliban – was successfully achieved within three months of the commencement of military action, the advertised long term goals- of eliminating the leadership and forces of Al Qaeda; and securing Afghanistan against resurgence of the Taliban or Al Qaeda- have remained elusive.

While Al Qaeda has been ‘degraded’ and was successfully prevented from attacking the American homeland again after 9/11, its leadership still remains at large and so does its ability to launch terror strikes of devastating impact- as it did in Madrid, London or Mumbai. The Taliban’s rule in Kabul was terminated but it still leads a brazen insurgency and controls vast swathes of Afghan territory, with explicit intentions of seizing power in the capital. It has also cloned a Pakistani sibling that controls vast tracts of territory in Pakistan and has the ambition-and possibly also the means- to capture power there. The success of the Taliban stems from different sources: in Afghanistan, from the fragility of state structures and in Pakistan from their Faustian complicity. The Government in Afghanistan plans democratic elections but its stability, absent western forces to prop it up, is suspect, as is its capability to provide meaningful governance to its people. In Pakistan, the government of the day is democratically elected, but with limited capacity to prevent its agencies from consorting with the Taliban.

This paper argues that the failure on the part of the US to achieve all its goals can be attributed largely to flawed strategies or incomplete adherence to sound ones. Also, many of the well-intentioned strategies lost potency when the war in Iraq claimed both the strategic attention of the leadership and a large chunk of finite military and intelligence resources. The paper examines the nature of the goals, strategies and objectives of US policy since 9/11, in the backdrop of Afghanistan’s tortured history. It looks at the literature on the effectiveness of various strategies (brute force, coercion, deterrence) deployed against terrorism or its state sponsors and argues for a wider, more broad-based ‘foreign affairs strategy’ to deal with terrorism in a regional context. It suggests that the conceptualisation of a counter-terrorism strategy as a global war on terror was flawed and led to confusion in defining both goals and strategies.

The paper also looks at the nature of the insurgency in Afghanistan and suggests that stronger efforts at nation building were required not just for better governance for humanitarian ends, but also to enhance security by countering the insurgency and eroding support for the extremists. It evaluates the case that US action in Iraq significantly diluted the effort in Afghanistan at a time when a surge in troops would have consolidated the gains better. It suggests that a more integrated regional policy, with stronger involvement of regional powers like India, Iran and Russia would have made for better policy. Besides, more focussed and harsher attention to Pakistan’s internal dynamics would have better exposed -and reversed- its complicity in sheltering extremists. The paper also looks at the latest strategy outlined by the Obama administration that reaffirms the core goal in Afghanistan and lays out a more comprehensive policy for achieving it.

In conclusion, the paper examines the counterfactual of an alternative strategy that would have brought the US closer to its goal. If the US had, in 2002, not let itself be distracted by the mirage of a Global War On Terror to be fought in Iraq and instead focussed on an international troop surge accompanied by a serious international reconstruction effort in Afghanistan; if it had followed an integrated strategy and involved regional players more; if it had created tougher conditions for Pakistan, coercing it to dismantle the terrorism infrastructure and deal with the extremists within its boundaries; US and Afghan interests would then have been better served.

Background: From The Great Chessboard To Grand Central Of Terror

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the ‘great game’ was played on the chessboard of Afghanistan and Central Asia, manifesting the strategic rivalry between the British and Russian empires. The deadly game continues to this day, involving an increasing array of actors from both within and without the chessboard. The Cold War that arose in the wake of the Second World War made Afghanistan the site of a bitter contest by proxy between the US and the Soviet Union.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 was a more direct intervention by a superpower that saw Afghanistan as its backyard. But this latest move met a response from the US in the shape of a covert ‘Charlie Wilson’s War’, which was fought through the secret supply of US funds and US – funded weapons (with shoulder-held ‘Stinger’ missiles serving as their proud mascot), for the Afghan mujahideen, and training and deliveries funnelled through the Pakistan military intelligence outfit, the Inter-Service Intelligence Directorate-ISI. The ISI in turn, in General Zia’s Pakistan, was significantly bolstered by this role and became a state within a state, with access to vast US funds and trust, both of which it continued to exploit well into the current decade. The bruising proxy battle broke the back of Soviet resolve; and Afghanistan- long believed to be the graveyard of empires- became a key factor in accelerating the demise of the Soviet Union. So the Soviet backyard was soon the graveyard and the consequent abrupt end of the Cold War left the US as the last superpower standing in the 1990’s.

But this unipolar moment was also marked by what can legitimately be described as the abdication of the US from Afghanistan, making it that country’s lost decade, causing a tremendous feeling of abandonment amongst moderates in the region. The US rapidly lost interest in the region and withdrew all direct support for Afghanistan. The vacuum left by an inward-looking US of the Clinton era spawned violent internecine tribal warfare which eventually led to the violent rise of the Taliban and its bloody takeover of Afghanistan.

Among the fighters who descended in the Afghan theatre for the US-financed jihad against the Soviets was Osama bin Laden, who later banded together several Afghan war veterans and founded Al Qaeda in Peshawar in 1988. Pakistan meanwhile continued to ignore history’s lessons about creating and feeding monsters, cultivated the Taliban (and even elements of Al Qaeda), as strategic assets to be used for insurgency and terrorism in India-particularly in Kashmir- and to provide Pakistan with ‘strategic depth’ to its West, in its contest with India. The Taliban, thus empowered, became a willing host of Al Qaeda; the two organisations were at the peak of their power and destructive potential in 2001, on the eve of 9/11.

Before the events of 9/11 shattered the calm, terrorism in the US perception appeared to be something that happened to generic others. Scholars debating the grand strategy for US foreign policy in the 1990’s failed to recognize the threat and “shared…a lack of concern about terrorism.” (Cronin, 2004). The picture looked remarkably different to countries that were victims of the terror emanating from the region. India, for instance, had been painfully aware of the global or trans-border dimension of international terrorism, with terrorist bombs in the border provinces of Jammu & Kashmir and Punjab reverberating through the 1980’s and 1990’s. Prime Minister Vajpayee of India had in fact presciently warned the US Congress in 2000 that distance offered little insulation against the terrorism being spawned in India’s dangerous neighbourhood. He said, “No country has faced as ferocious an attack of terrorist violence as India has over the past two decades: 21,000 were killed by foreign sponsored terrorists in Punjab alone, 16,000 have been killed in Jammu and Kashmir…Distance offers no insulation. It should not cause complacence.” (Congress, 2000).

It took four jet planes and a handful of fanatics on a fine September morning to position global terrorism as the central focus of US foreign and security policy. 9/11 was to become in several ways a seminal moment not just in the evolution of the US policy mindset, but also in the way the US perceived the rest of the world. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates admitted in a TV interview with Fareed Zakaria (Gates, 2009) that the US had been in a state of denial about the destructive potential of Al Qaeda in the 1990’s, not unlike the authorities in Pakistan in the present day. While Al Qaeda had declared war on the US by perpetrating acts of terror from 1993 (for example, the bombing of the World Trade Centre in 1993, the attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998), the US returned the favour only after 9/11.

Post 9/11 US Policy on Afghanistan: Lofty Goals And Strategic Feints

In analysing the goals, strategies and objectives of US policy, it would be useful to first lay down the definitions of these terms, frequently deployed interchangeably in academic and journalistic writing and often conflated in practice. Terry Deibel, guru of American statecraft, defined strategy broadly as a “plan for applying resources to achieve objectives.” (Deibel, 2007). Deibel usefully examined the many meanings of strategy, drawing distinctions between military strategy, security strategy, grand strategy and foreign affairs strategy, and positing a hierarchy between them. Deibel suggested that instead of stretching national security strategy into non-security realms, it would serve function better to conceive of ‘foreign affairs strategy’ as encompassing goals, security-related or not, that serves the nation’s interests in its external relations. This is an important distinction for Afghanistan where a Pentagon-led military strategy was often conflated with a foreign affairs strategy. Another useful distinction that Deibel drew was between policy and strategy: policy, he averred, was best defined as the ‘statements and actions of Government.’ In this conception, strategy is an input to the process of policy making within Government; as an input, it may flow from the political leadership or in competing versions from alternative sources, like think tanks and academia.

Given the multiplicity of terminologies, we can draw on a simple definitional model for the purposes of describing Afghanistan policy in this paper:

First, Goals are broad desired outcomes (say, ending Taliban rule in Afghanistan).Second, Strategies are approaches to meet goals (using brute- military force and an alliance with insurgents in the North). Third, Objectives are measurable steps to actualise strategies (capturing Kabul before winter). Fourth,Tactics are the tools to achieve objectives (limited ground troops with heavy air support). Fifth,Policy comprises statements and actions of Government (Global War on Terror.)

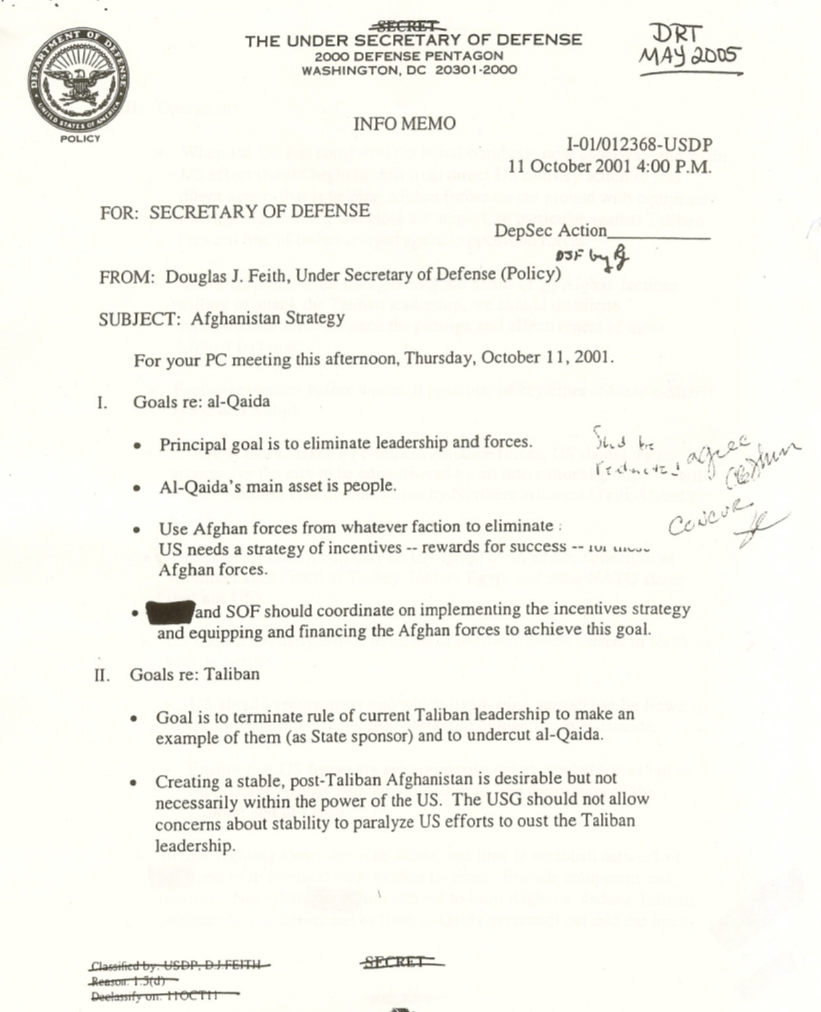

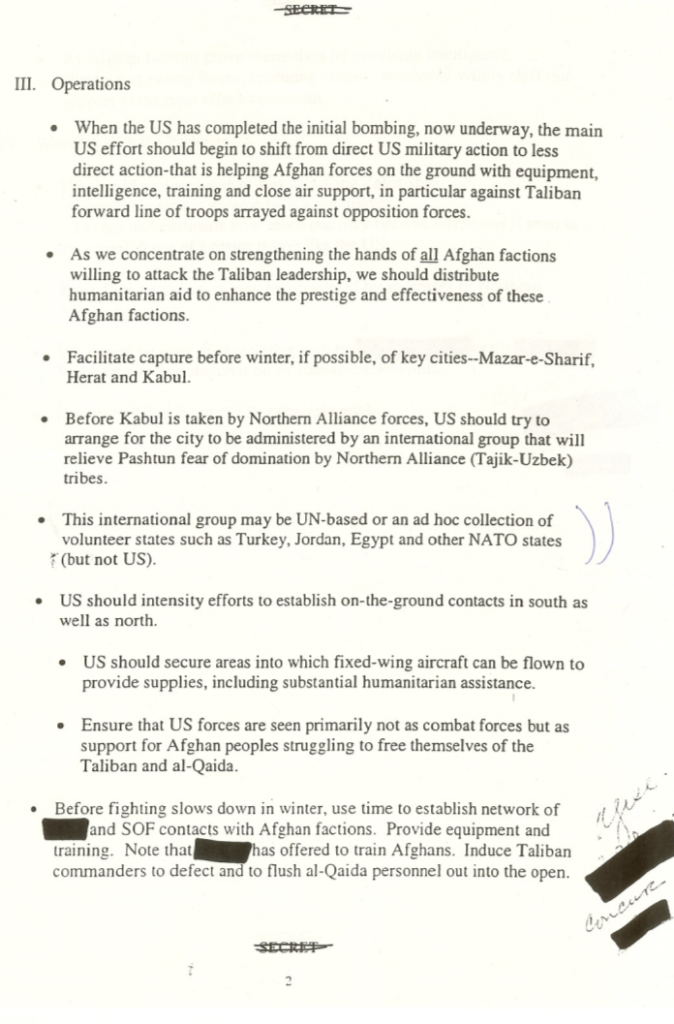

In 2001, an internal Pentagon memo, since made public, outlined two principal goals for the US in Afghanistan: first, to eliminate the leadership and forces of Al Qaeda; and second, to terminate the rule of the Taliban leadership. The memo, attached at Appendix I, explicitly stated that nation building was not a key strategic goal for the US. It clarified that creating a stable, post-Taliban Afghanistan was desirable but “not necessarily within the power of the US.” It suggested the US should not allow “concerns about stability to paralyze efforts to oust the Taliban leadership.” While the second goal was readily achieved by military means in 2001, the first has clearly met with only partial success, with bin Laden and much of the Al Qaeda leadership still at large in the tribal badlands of Pakistan.

The conceptualisation of Afghan policy within the larger Global War on Terror (GWOT) led rhetoric to trump substance. It was hard to pin down a strategy on a goal the 2002 national security strategy (NSS 2002) described simply as “defeating terrorism”. With the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the goals became more diluted and even less specific. The 2006 national strategy for combating terrorism (NSCT 2006) set up an aspirational goal to “ultimately win the long war and defeat the terrorists and their murderous ideology.” Similarly, the 2006 security strategy (NSS 2006) outlined a long-term goal to “win the war on terror by winning the battle of ideas.”

The core goal of US strategy in Afghanistan was later refined and articulated with greater clarity: Defense Secretary Robert Gates told the Senate in January, 2009, that “our primary goal is to prevent Afghanistan from being used as a base for terrorists and extremists to attack the US and its allies.” The latest public expression of the primary goal by the Obama administration is much the same, except that it recognizes that terrorist safe havens have moved to Pakistan and that the status quo (of keeping the Taliban out of power) must be sustainable. The White Paper on Afghanistan and Pakistan (Inter-agency group, 2009) released in March 2009, suggests that the core goal of the US must be to “disrupt, dismantle, and defeat Al Qaeda and its safe havens in Pakistan, and to prevent their return to Pakistan or Afghanistan.” While the Obama administration has been careful about keeping the core goal consistent and well defined, it has articulated a more comprehensive strategy than that of its predecessor.

While the primary goal of US foreign affairs strategy in Afghanistan has been refined with each articulation, it has remained largely consistent, even with the change in administration. However strategies to achieve this goal have often been inconsistent and incoherent or partially implemented and have resulted only in partial success, as measured by the outcomes. Moreover, the approach since 9/11 saw an inordinate focus on military strategy and was not accompanied by a more general, broad-based ‘foreign affairs strategy.’

To meet the central goals in Afghanistan in 2001, viz terminating Taliban rule and defeating Al Qaeda, the main elements of the US strategy, as explicitly stated, or implicit from the implementation, were:

First, Military action to remove the Taliban from power in Kabul. Second, Regime change in Kabul, by facilitating the installation of a US-friendly Government. Third, A relatively small presence of US and NATO forces to maintain the status quo. Fourth, A global war on terror to be fought, wherever required, (mainly in Iraq). Fifth, Diplomatic engagement with Pakistan to provide staging areas for action and help in fighting Al Qaeda and Taliban.

These key strategies failed to include nation building or significant reconstruction. While nation building was clearly not a goal, we will demonstrate it should have been a key element of strategy to make the goal of sustaining regime change and reversal of Taliban rule more durable. Equally, it was poor strategy to keep a limited Western force to maintain the status quo. Viewed through the prism of the goal in Afghanistan, the strategy to open a front in Iraq was flawed, since it diverted resources and strategic leadership, making it harder to fight the resurgence of the Taliban and Al Qaeda or even creating conditions for that resurgence. Also, the war in Iraq was spuriously linked to Afghanistan as part of the GWOT, whereas it was based on a separate set of justifications based on Weapons of Mass Destruction and the internal nature of the Saddam regime. And finally, the strategy on dealing with Pakistan was unsound since it failed to take into account the extent to which parts of the Pakistani state were compromised vis-à-vis the Taliban. We flesh out each of these propositions in subsequent sections.

US Strategies: Coercive Diplomacy, Brute Force and Beyond

In 2001, the US joined an existing alliance between India, Russia and Iran, supporting the Northern Alliance of Tajik and Uzbek rebels, to overthrow the Taliban regime. Some 350 US Special Force soldiers, aided by 15000 Afghans overthrew the Taliban regime in less than three months while suffering about a dozen US fatalities. Some 100 US combat sorties a day helped them along in this task.

In his influential theoretical construct, Thomas Schelling distinguished between unilateral ‘brute’ force (concerned with enemy strength) and coercion (concerned with enemy wants and fears) based on the power to hurt (Schelling, 1966). In terms of Schelling’s framework, the US strategy was to deploy brute force to achieve its goal to alter the status quo, viz to oust the Al Qaeda-friendly Taliban regime. The brute force strategy was however preceded by one of ‘coercive diplomacy’, when the Taliban was given a deadline to hand over Al Qaeda to the US along with a credible threat of force in case they did not alter their behaviour. The coercive diplomacy failed-it had several sticks to offer but was short on carrots. Posen has pointed out that even after the first five days of air strikes, in his press conference of October 11, President Bush gave the Taliban a “second chance” to turn over bin Laden and evict his organisation from Afghanistan (Posen, 2001). Once the Taliban declined the opportunity to co-operate, the US had no choice but to wage war on them with the objective of driving them from power. It is debatable if this gesture was a tactic in administering calibrated doses of brute force or an attempt to use coercion.

P.V. Jacobsen (Jacobsen, 2007) seems to believe it was the latter, given the way he ‘typed’ the development in his study. Jacobsen, who rigorously studied the deployment of coercive diplomacy against state sponsors of terrorism, suggested that from 1990-2005, Western states used coercive diplomacy against state sponsors of terrorism and Al Qaeda on nine occasions, with limited success. In Afghanistan, this policy failed against Al Qaeda and the Taliban on three occasions. In Round 1 (1998-2001), the demand was for the Taliban and Al Qaeda to stop support and use of terrorism and hand over bin Laden. Non-compliance was met with sanctions and an attack with 60-70 cruise missiles. In Round 2 (September- October 2001), the demand was to stop supporting and using terrorism and hand over Al Qaeda leadership. The threat of use of brutal force in case of non-compliance was credible. A failure of the policy led to an escalation to limited force. In Round 3 (October 2001) a final appeal was issued to the Taliban to hand over the Al Qaeda leadership. The stick was war and the carrot for altered behaviour was survival. When the policy failed, full-scale force was deployed. Clearly, with the failure of coercive diplomacy, the US had no option but to deploy brute force. But would coercion and deterrence never work under any circumstances when a nation-state is faced with rogue states sponsoring or shielding extremists? Brad Roberts of the Institute of Defence Analyses has examined this issue -whether deterrence could work even in the war against terrorists when faced with an organisation like Al Qaeda (Roberts, 2003). He argues that terrorist organisations, as a generic type, are best described as “complex adaptive systems”, which encompass many actors beyond the bomber and his leader. He suggests that as a complement to strategies emphasising offence and defence, deterrence-or some strategy approximating it- may have a role to play. The constellation of sponsors, enablers and assets may provide opportunities on this count. Putting these state sponsors and enablers at risk is in obvious point of attack and could be a focus of policy. The final verdict of the RAND study that Roberts contributed to is that, in this context, “a strategy of deterrence is the wrong concept—it is both too limiting and too naive. It is far better to conceive a strategy with an influence component, which has both a broader range of coercive elements and a range of plausible positives, some of which we know from history are essential for long-term success.” (RAND, 2002)

This is precisely the challenge the US faced in both Afghanistan and Pakistan after brute force had ousted the Taliban regime. A more nuanced strategy of “influence” on sub-national actors, with coercive elements and plausible positives, was required to be deployed in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. But the actual policy response was not particularly nuanced, was controlled by the Pentagon and was overly dependent on brute force. Significantly, with NSS 2002, the US publicly rejected the strategy of deterrence and defense, which had dominated defense discourse and policy during the Cold War years, for an offensive, pre-emptive strategy against hostile states and terrorist groups.

Terror: The Elusive Enemy

The Global War on Terror was probably a useful rhetorical device, but as it wound its way into policy documents, it fogged up objectives and confused strategy. Richard Betts has argued that terrorism is a tactic, not an enemy (Betts, 2002). The war had to be fought with political groups who use tactics of terror. The framing of the Afghanistan action under the rubric of the war on terrorism was itself an example of policy that became a victim of its own rhetoric. Some observers have pointed out that it had no more legal or operational significance than the rhetorical wars on cancer, drugs or poverty. Terrorism, goes the legal argument, cannot be a party to a conflict; and it is not a nation state, so no war can be waged against it.

Terror tactics could in fact be looked at as a strategy of coercion on the part of its users. It could be argued that Al Qaeda was making a point of this nature to the West with the 9/11 attacks– if you do not reduce your global role and abandon your presence in Israel and the Persian Gulf, clear troops from our holiest lands in Saudi Arabia and reign in the evil influence of Western culture on Islam, we will attack you again. This was thus an attempt at coercion by demonstrating the use of force and the implicit threat of its use again in the future.

Betts has argued that “American global primacy” is one of the causes of terrorism because it animates both the terrorists’ purposes and their choice of tactics. He suggests that the strategy of terrorism is most likely to flow from the coincidence of two conditions: intense political grievance and gross imbalance of power. Either one without the other is likely to produce either ‘peace’ or ‘conventional war’. Under American primacy, users of terrorism suffer from grossly inferior power, by definition. That should focus attention of policy on the political causes of their grievance or at least encourage a more comprehensive strategy of dealing with political and economic grievances, aside from the use of force.

In an article written soon after the 9/11 attacks, Barry Posen argued that the struggle against terrorism had serious implications on overall US policy (Posen, 2001). The US needed a grand strategy of ‘selective engagement’ in a sustained counterterrorism offensive. In this strategy, US power is meant to reassure the vulnerable and deter the ambitious. Posen warned with uncanny prescience against the hijacking of the agenda by ‘primacists’ like Paul Wolfowitz, who was suggesting that 9/11 offered the US the opportunity to establish its primacy in the Middle East as well. The war against Al Qaeda was necessary, in Posen’s scheme, because bin Laden and others like him would continue to attack the United States so long as it asserted its power and influence in other parts of the world. Posen suggested that since the two main adversaries in the fight against terrorism were the extended Al Qaeda organisation and the states that supported it, the policy objective would be to induce the States to change their practices through more broad- based means such as persuasion, bribery or non-violent coercion.

Thus, both Betts and Posen were prescribing more nuanced strategies beyond the exercise of brute force, for tackling terrorism. Mainstream US literature in fact looks at another causal variable and suggests that failed states are what terrorism feeds on. The corollary is that good governance will always be an important element of a counterterrorism strategy. This hypothesis would suggest that Osama bin Laden was looking for failed states to plant his toxic ideology in, and to use as a safe haven for launching his war against the West. So, Al Qaeda was essentially an ideology in search of a failed state. It had moved from Somalia to Sudan and had struck firm roots in Afghanistan and then Pakistan. It could be weakened by its defeat in Afghanistan and Pakistan but it would not go away altogether. However, preventing key states from failing would pull the plug from the incubator.

The conceptualization of the GWOT clearly added little to the policy world beyond the rhetoric. Experts point out that the US faced a number of different insurgencies around the globe – some with local causes, some transnational. Viewing them all through one lens would tend to distort the picture and magnify the enemy. In Afghanistan, the US was fighting Al Qaeda and its allies, not a global beast with a single brain and purpose.

In sum, the literature would suggest that fighting an enemy given to deploying terror tactics requires a comprehensive strategy in a regional context that would move beyond brute force and would include nuanced political and economic elements, apart from military means. A possible component of such a strategy would be to bolster governance in states that were prone to failing and also prone to hosting toxic ideologies.

Limitations Of Brute Force: Insurgencies And Governance

It is useful to draw the distinction between terrorism emanating from the larger region and insurgency within Afghanistan. The use of military power was effective in securing regime change but not in warding off any challenge to the revised power equations. Seth Jones has pointed out that the Afghan insurgency grew as the Taliban and other insurgents began a sustained effort to overthrow the Afghan Government (Jones, 2008). The insurgency and the violence were particularly acute between 2005 and 2006, when the number of suicide attacks jumped up from 27 to 139. Jones has argued that a precondition for the onset of the Afghan insurgency was structural: the collapse of governance after the overthrow of the Taliban regime.

In Jones’ conception, insurgencies are triggered by grievances, greed or ideology. He argues that internal anarchy within countries, analogous to the one prevalent in the international sphere, creates a fertile ground for insurgencies to challenge the status quo. In the case of Afghanistan, the argument would go, a Jihadist (Al Qaeda) and a fundamentalist (Taliban) ideology found a fertile ground in a failed state; the leaders of the insurgency in Afghanistan were in fact motivated by an extremist Sunni ideology. Second, the collapse of governance is a critical precondition for the onset of insurgencies: this was true of Afghanistan. The overthrow of the Taliban government led to emerging anarchy. Therefore, as a policy remedy, it would be important to improve governance and essential services and the effectiveness of the Afghan police in rural areas of the country to have stabilising effect over the long run. This would likely undermine the Taliban support base and increase the government’s monopoly of the legitimate use of force within Afghanistan.

Like Betts and Posen did for countering terrorism, Jones thus suggests a largely political response to counter an insurgency.

Nation Building -Strategy To Counter Insurgency and Terror?

Both the nature of the terrorist enemy residing in a failing host state and the character of the insurgency would suggest a need for a credible strategy of nation building and reconstruction. Most writing on policy to deal with terrorism is consistent with this thesis. However, in a context such as Afghanistan, any large-scale nation-building effort needed to be accompanied by a strong force presence creating conditions for civilian reconstruction teams to work in relative security.

Sceptics of nation building worry about imperial over-reach (for example, the US spreading itself thinly on every global problem including Somali pirates and Iraq and North Korea) or mission creep (when finite resources compete for fulfilling several non-core objectives). However, the case for nation building and governance support in Afghanistan is not part of the argument to rescue every failed or failing state because of their potential to host extremists. It is a case for a concerted and sustained effort in a theatre where US enemies are already present and risks are concentrated. To put it simply, Afghanistan needs nation building more for security than humanitarian reasons. It needs the effort because Al Qaeda struck from there. Barnett Rubin illustrates this point dramatically, when he points out that if the revealed preference theory from economics is borrowed and deployed in this case, till September 11, 2001, Afghanistan was worth $100 million a year to the world, measured in terms of the humanitarian aid commitment of the global community. Its value shot up to about $15 billion a year, simply because Al Qaeda attacked from its territory (Rubin, 2009).

But clearly, much more effort is required. In his authoritative book on Afghanistan, ‘Descent into Chaos’, Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid has argued that solving the problems of the region required a Western led Marshall plan for Afghanistan and a commitment that would have to be measured in not months or years but decades (Rashid, 2009, p. 132). An unfaltering western military presence was crucial in creating the basic security for this effort. Ending the failing state syndrome in the region required massive aid, internal economic reforms, democratisation and literacy, and these goals needed sustained civilian commitment, apart from the inevitable military presence.

The US missed a crucial opportunity to kick off a massive international reconstruction effort in 2002. By that year, the warlords in Afghanistan were becoming stronger while the Karzai regime lacked the resources to compete with them. Rashid has argued that the US strategy effectively left Karzai emasculated in the capital, protected by foreign forces, while relying on the warlords to keep peace in the countryside and the US special operations forces (SOF) to hunt down Al Qaeda. He argues that the US deployed “a minimalist, military intelligence driven strategy that ignored nation building, creating state institutions or rebuilding the country’s shattered infrastructure. By following such a strategy, the US left everything in place from the Taliban era except for the fact of regime change.” A strategy of serious nation building at this stage could have involved the global donor community. The US could have started building the economy and the army to reduce the influence of the warlords. Rashid has dubbed this the generic ‘warlord strategy’, which was ill advised and came with high long run costs. A similar strategy was to be ‘recast in Iraq in 2003, when the US disbanded the Iraqi army and then preferred allowing Shia warlords to mobilise militias rather than to rebuild state structures’ (Rashid, 2009, p. 133). The pointed aversion to national reconstruction thus seems to have been a matter of avowed policy.

Most Afghanistan experts on the ground in the 2000s emphasise this point of a grossly under-funded reconstruction effort in Afghanistan. Francis Vendrell who was the UN Special Representative in Afghanistan after 9/11, has argued that the Afghan public was prepared for a much higher level of international nation-building effort as also international tutelage for their political processes (Vendrell, 2009). Similarly, Robert Finn, the first US Ambassador in Afghanistan after 9/11, supports the view that development needed to come one kilometre behind the troops, to make any impact on the Afghan people. He felt that Tajikistan could be held up as a model for Afghanistan, where the decline into chaos was provided by strong economic projects like pipelines and roadways (Finn, 2008). The UN representative Brahimi had promised what he termed a ‘light footprint’ for the UN presence in Afghanistan, while some US officials promised they would carry out ‘nation building lite.’ However, the tread was too feather-footed to be noticed or to make any positive impact on the lives of poor Afghans and hence on consolidating security gains. Effectively, the US failure to embark on a serious nation-building program involving the international community, signalled to the UN and other partners that the US was distracted- and an opportunity was missed for several years. Preventing the emergence of terrorist safe havens in the future required a long-term commitment by the US to high impact reconstruction and grassroots nation-building in Afghanistan. This did not mean that the resources would all have come from the US: the global community, including the UN, NATO and the World Bank, and all regional players, could have been involved in this exercise.

Afghanistan Strategy Could Not Work In Isolation

The strategy for Afghanistan necessarily had to be a part of a broader strategy for the region comprising Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia. The strategy also needed to be seen in concert with the counterterrorism strategy, then dubbed the GWOT. Apart from integrating elements of the Afghanistan, Pakistan and counterterrorism strategies (now helpfully re-christened ‘Af-Pak’), the strategy needed to integrate elements of US external relations with India, Russia, Iran and China. Coordinating US policy with India was particularly critical given India’s strategic interest in the region, its vulnerability to the terrorism emanating from there and its long-standing historical ties with Afghanistan, which made it one of the strongest donors for Afghanistan’s reconstruction.

Barnett Rubin has pointed out that in 2001, the US joined an existing coalition – the Northern Alliance (comprising largely ethnic Uzbeks and Tajiks), supported by India, Iran and Russia, fighting the Taliban, which had been backed by Pakistan (Rubin, 2009). The US strategy was overly focussed on turning Pakistan to its side, and failed to coordinate policy responses with other regional players in a consistent or structured way. Somewhat inexplicably, Iran was consigned to the ‘axis of evil’ soon thereafter and an opportunity to coordinate with Afghanistan’s western neighbour was lost.

Iraq- The Distracting Side Show

While it is not the purpose of this paper to contest the justification for the Iraq War, it had an unmistakably profound impact on both the strategy for and implementation of the Afghan project. Even attempts to achieve the primary goal of the US – hunting down and eliminating Al Qaeda – were derailed, as the war in Iraq sucked out the prime US instruments from Afghanistan. Rashid has listed the critical resources that were pulled out from Afghanistan with unseemly haste: “General Tommy Franks began moving his best intelligence assets out of Afghanistan and to the Iraq Theatre. The specially constituted Task Force Five, made up of some 150 SOF, who were hunting for bin Laden, was moved in its entirety to Iraq, while another 150 SOF troops were cut to 30. General Franks also sent home the B-1 bombers based command whose smoke trails across the Afghan skyline had signalled the omnipresence of US power… The CIA closed its forward bases in Herat, Mazhar-e-Sharif, and Kandahar and postponed the $80 million refit of the Afghan intelligence service…satellite surveillance of Afghanistan and the use of drones and other technological spying facilities were first reduced and then withdrawn. Junior US officers were quoted as saying that General Franks believed the job in Afghanistan had been done (Rashid, 2009, p. 134). Ryan Crocker, the US Charge d’affaires in Kabul was reported to have said, “Pentagon’s view was that our job is done and let’s get out of here. We got rid of the evil and we should not get stuck.”

Policy makers seemed to get it wrong on both counts: the evil still resided in the safe havens of the region and the US was already stuck in the Afghan theatre. Several observers have pointed to the irony of US repeating in Iraq the mistakes made in Afghanistan. Rashid makes this point insistently: “First, in Afghanistan, and then in Iraq, not enough US troops were deployed, nor was enough planning and resources devoted to the immediate post-war resuscitation of people’s lives. There was limited coherence to US tactics and strategy, which led to a vitally wrong decisions being taken at critical moments – whether it was reviving the warlords in Afghanistan or dismantling the army and bureaucracy in Iraq.”

More importantly, the infusion of financial resources into Iraq made the abandoning of nation building a fait accompli in Afghanistan. The billions spent in Iraq were the billions that were not spent in Afghanistan. Moreover, as Rashid has suggested, the US attack on Iraq convinced Pakistan that the United States was not serious about stabilising the region, and that it was safer for Pakistan to preserve its own natural national interest by clandestinely giving the Taliban refuge.

2002-03 was an opportune moment to consolidate the gains in Afghanistan and step up the force presence south of Kabul. This could easily have been accomplished by expanding the International Security Assistance Force-ISAF. Several European powers seem to have offered to send troops for this purpose for what they saw as a legitimate war. In contrast, the war in Iraq was divisive and the US intention to invade Iraq not only split the international community over the Middle East, the disagreements started cracking up the joint efforts to build Afghanistan.

Rashid avers that with Iraq on his mind, Rumsfeld seemed ‘tone deaf’ to the regrouping of the Taliban and Al Qaeda. In 2003 he arrived in Kabul to declare the end of combat operations against the enemy, even as a new war in Iraq was underway. The Taliban was however rapidly regrouping and by the summer of 2003, one or two attacks by the Taliban occurred every other day(Rashid, 2009, p. 246). Al Qaeda also put itself back on the world’s agenda in March 2004, with the bombing at the railway station in Madrid that killed 192 people and wounded more than 1600, the most devastating terrorist attack in Europe since World War II.

The war in Iraq was thus launched, shifting strategic attention and resources from Afghanistan, leading almost directly to resurgence in the activities of the Taliban and Al Qaeda, and a sudden loss of interest on the part of the US in increasing troops or attempting to push reconstruction. Moreover, Pakistan continued consorting with the extremists, to use them as potential assets in its own security game. Clearly, the Afghanistan project received a major setback as the US took its eyes off the ball.

Pakistan: The Solution Or The Problem?

The US has had a long-standing problem of abrupt attention deficit in Afghanistan. With the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan and the end of the Cold War, it was not just Afghanistan that the US took its eyes off, all of South Asia slipped off its radar, even though India, and particularly Kashmir -was suffering a terrible decade of terrorism and insurgency which ran from 1989. Not without coincidence, the insurgency in Kashmir began the same month as the Soviet troops left Afghanistan; it was almost as if the handlers of the jihadist fighters transferred them seamlessly from the West of Pakistan to its East. From most accounts, US intelligence was well aware that Al Qaeda and the Taliban had taken over the training of Kashmiri militants in Afghanistan after 1997 and were promoting the jihad in Kashmir as part of the global jihad.

In 2002, the contradictions in Pakistan’s counterterrorism strategy were becoming glaring(Rashid, 2009, p. 155). Even as the ISI helped the CIA run down Al Qaeda leaders in Pakistan’s cities, Pakistani Islamist militants, with quiet ISI approval, were attacking Indian troops in Kashmir or helping the Taliban regroup in Pakistan. At the same time, Al Qaeda itself was involved in training and funding the Islamist militants who were ordered to kill Musharraf. Pakistan’s regime continued to differentiate between the good jihadis, who fought in Kashmir on behalf of the ISI, and the terrorists, who were largely Arabs, but such differences had in actual fact long ceased to exist. In a briefing, Musharraf divided the extremists into three groups – the Al Qaeda – Taliban, the Pakistani sectarian groups, and the Freedom Fighters of Kashmir. The military was clearly signalling that it still considered some jihadis as acceptable and was maintaining links with them. Rashid quotes a Pakistani General as telling him with brutal honesty that it was not possible to completely crackdown on the fundamentalists, as they may be needed in any future conflict with India.

The Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan had become terrorism central, providing training and manpower for the insurgency in Afghanistan and pushing forward the Talibanisation of the NWFP, while guarding the sanctuaries of Al Qaeda where international terrorists were trained. Almost all latter-day Al Qaeda terrorist spots around the world had a FATA connection, intelligence reports have confirmed. The four suicide bombers who carried out the attacks on the London Underground in July 2005 were connected to FATA. The ringleader, Mohammed Siddique Khan, visited FATA in 2003 and 2004, when he had some contact with Al Qaeda figures and “some relevant training”, according to a British government report. Pakistan continued to be in denial, with Musharraf insisting that “law enforcement agencies in Pakistan had completely shattered Al Qaeda’s vertical and horizontal links and smashed its communications and propaganda set up.” (Rashid, 2009, p. 278)

Rashid paints a detailed and credible picture of Pakistan’s complicity in the rise of the Taliban: “The Pakistani branch of the Taliban expanded across northern Pakistan much faster than anyone expected. It was not so much their successful strategy as the double-dealing carried out by the army, the ISI, and Musharraf. The Al Qaeda leadership was already living on the Pakistan side of the border, but with the creation of the Pakistani Taliban, terrorist groups received another layer of protection and more opportunities to expand their influence, base areas, and training camps deeper into the heart of Pakistan’s populated northern regions… the army’s insecurity, which has essentially bred a covert policy of undermining neighbours, has now come full circle, and threatens to undermine Pakistan itself.” (Rashid, 2009, p. 400)

Most intelligence assessments suggest that Mullah Omar and the original Afghan Taliban Shura still live in the Baluchistan province of Pakistan. Afghan and Pakistani Taliban leaders continue to thrive in FATA where Al Qaeda also has a safe haven along with a platform for the Central Asian, European and Arab extremist groups who are expanding their reach into Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Most experts share this assessment of the rise of extremism in the region. According to the Task Force of Afghanistan experts set up by the Asia Society (Asia Society, 2009), the US did not match its proclaimed objectives with the necessary resources and strategic effort. Its dysfunctional relationship with Pakistan exacerbated regional tensions, failed to prevent Al Qaeda from re-establishing a safe haven in Pakistan’s FATA, enabled the Taliban to regroup and rearm from their strongholds in Quetta and FATA, and offered no significant response to the upsurge of the Pakistan Taliban movement.

The Task Force points out that for years, Pakistan has been used as a base of international terrorism by Al Qaeda and its allies. After 9/11 and particularly after the US operations in Afghanistan, Al Qaeda had no bases in Afghanistan, and no international terrorist attack has been traced to Afghanistan. Instead, Al Qaeda has established a new safe haven in the tribal agencies of Pakistan and most terrorist attacks since 9/11 have been traced to FATA.

The most critical point made by this expert assessment is that the infrastructure for terrorism is common. It suggests, “the use of armed extremist groups for asymmetrical warfare to confront threats from the larger countries has created a military – extremist – industrial complex in Pakistan. The November 2008 Mumbai attacks appeared to have been carried out by organisations that form or part of this complex. Pakistan’s military and intelligence agencies continued support for selective elements in this complex such as the Afghan Taliban and the fighters in Kashmir. They have created an infrastructure that is used by all of these organisations, including Al Qaeda. The expansion of Taliban control in northwest Pakistan is threatening the main NATO and US supplies to Afghanistan (Asia Society, 2009, p. 16).

Highly trained and motivated individuals from this region have already wrought terror in Europe and in India. They would only need an extra degree of innovation and luck to strike in the US homeland, for example, using a dirty bomb to attack a US city. Pakistan would therefore need to redefine its security paradigm to look at armed extremists as a threat rather than an asset. Pakistan must feel the weight of the international community to dismantle the infrastructure of terrorism and to stop making the distinction between good terrorists and bad terrorists. US aid to Pakistan needed to be conditional to a series of actions, including dismantling the terror infrastructure and claiming complete control over its territory in FATA.

Is It Really Worth US Effort: Early Exit Or Long Haul?

Not everyone is convinced that Afghanistan is worth the candle. The counterview is provided by political scientist John Mueller, of Ohio State University, who has suggested that Afghanistan is the wrong war since the dangers posed by the Taliban and Al Qaeda are overblown (Mueller, 2009). He suggests that just like the war in Iraq was fought on the pretext of Saddam Hussein holding weapons of mass destruction, the perpetuation of the war in Afghanistan is being based on the dubious arguments about the danger posed by the Taliban and Al Qaeda. He argues that Taliban was a reluctant host to Al Qaeda in the 1990s and felt betrayed when the terrorist group repeatedly violated agreements to refrain from issuing inflammatory statements and fomenting violence abroad. He suggests that given the limited interest of the Taliban outside the ‘Af-Pak’ region, if they came to power again, they would be highly unlikely to host provocative terrorist groups whose actions could lead to another outside intervention.

This argument would suggest that we see these terrorists for the “small, lethal, disjointed and miserable opponents” that they are and not over-estimate their destructive power. Mueller points out that President Obama has emphasised the humanitarian element of the Afghanistan mission as well. While the concern is legitimate, Mueller argues that Americans would be far less willing to sacrifice lives for missions that are essentially humanitarian than for those that seek to deal with the threat directed at the US itself.

Mueller’s suggestion that the Afghanistan war would ultimately be based on humanitarian rather than security justifications is spurious: it simply underplays the credibility of the threat emanating from Al Qaeda and the complexity of the regional interplay of forces. While it is reasonable to suggest that the probability of an attack on the US homeland from Al Qaeda based in Pakistan is low, the downside risk of such an event calls for an aggressive policy of intervention.

Obama Strategy: Towards Hope

The ‘White Paper’ and repeated articulations by the Obama administration are pointedly ‘on-message’ as they articulate the core goal of the US in Afghanistan: to “disrupt, dismantle, and defeat Al Qaeda and its safe havens in Pakistan, and to prevent their return to Pakistan or Afghanistan.” The paper also outlines “realistic and achievable objectives”. Though these ‘objectives’ marry both strategies and objectives in terms of the framework defined earlier, they do make for a comprehensive ‘foreign affairs strategy’ approach:

• Disrupting terrorist networks in Afghanistan and especially Pakistan to degrade any ability they have to plan and launch international terrorist attacks.

• Promoting a more capable, accountable, and effective government in Afghanistan that serves the Afghan people and can eventually function, especially regarding internal security, with limited international support.

• Developing increasingly self-reliant Afghan security forces that can lead the counterinsurgency and counterterrorism fight with reduced U.S. assistance.

• Assisting efforts to enhance civilian control and stable constitutional government in Pakistan and a vibrant economy that provides opportunity for the people of Pakistan.

• Involving the international community to actively assist in addressing these objectives for Afghanistan and Pakistan, with an important leadership role for the UN. The paper also emphasizes a regional approach and significant foreign assistance for ‘civilian efforts.’

The view from the ground supports this approach. Milton Bearden, a retired CIA station chief in Pakistan in the 80s has argued in Foreign Affairs that the war in Afghanistan has been an orphan of US policy (Bearden, 2009). Bearden has commended Obama’s new policy for not speaking of an early US exit strategy. He suggests that if the US were to declare an exit strategy upfront, it would make the already long war even longer. On the fear that the Obama strategy risks putting the US deeper into the bog of Afghanistan, he suggests that the US is already about as deep in the Afghan bog as a foreign military enterprise can get.

Bearden suggests that with a military solution effectively out of reach, the immediate task for the Obama administration would be to redefine its mission. The first step would be to reclassify its adversaries in Afghanistan. Committed Al Qaeda fighters should be shown no quarter. However the Taliban are a motley bunch and range from irreconcilable fanatics to narcotraffickers to bored punks carrying Kalashnikovs for less than $10 a day. Although a small percentage of hardened fighters may need to be hunted down, most Taliban members and sympathisers could be viewed as targets for reconciliation. Bearden has a point but these are operational choices which should be Afghan-led and made with caution. Reconciling with ‘moderates’ is always a risky policy and should be accompanied by checks and balances, for instance a policy of ‘locking in’ the reconciled in safe civilian jobs.

While the policy should be judged by its implementation down the line, the start is promising. US strategy in Afghanistan finally looks capable of correcting the three decades of bad policy choices inflicted on the Afghan- and also the American- people.

Conclusion: A Comprehensive Strategy To Undo The Damage

A significant opportunity was lost by the US around 2002, to consolidate the initial military gains and set Afghanistan on the path to security and reconstruction, while dealing a more decisive blow to Taliban, Al Qaeda and their terrorist havens. While the counterfactual cannot be conclusively demonstrated, an alternative strategy which would have helped the US obtain its goals in 2002, would have involved a US-led troop surge in Southern Afghanistan and near the FATA border and a more aggressive Pakistan policy that would have coerced Pakistan into claiming military sovereignty over its entire territory, flushing out radicals from their safe havens and dismantling the infrastructure to train terrorists.

An international force would have provided security for a strong international military-civilian effort at reconstruction. All regional players and particularly India would have been involved in an integrated regional strategy of security and nation building. Iran would not have been consigned to the axis of evil and involved in the regional strategy. Military and financial resources would have been available by shelving the Iraq project and attempting to achieve goals there through coercive diplomacy rather than brute force. In the 1980’s, the US became the principal financier of a dangerous jihad, which empowered the likes of Osama bin Laden. While that proxy war possibly served the goal of containing and humiliating the Cold War rival, it came with a very heavy price tag of destroying Afghan political and economic structures and destabilising the region.

The error was compounded in the 1990’s by a policy of abdication, which led to the rise of the Taliban, which in turn cradled Al Qaeda and its ambition of global jihad and allowed it to launch a successful attack on the US. In the 2000s, US interest in the region seemed to flag after its military reaction to 9/11, allowing the authority of the Taliban regime to be eroded, the warlords to reign unhindered and Taliban to regroup and re-emerge in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. The US now has the opportunity to lead the global community in significantly enhancing military presence and launching a strong international reconstruction effort, involving all regional players. The revised strategy of the new administration is promising.

XXX

Date: May 06 2009

This research article was submitted by Ajay Bisaria for his Masters in public policy at Princeton University.

APPENDIX I